Civil Rights Study Trip Reflection

In November, Hispanics in Philanthropy (HIP) & ABFE shared a week exploring the Civil Rights movement in a collective journey to Atlanta, Georgia, and Montgomery, Alabama. Together, we dove deeper into the past and the present systems and policies that have hindered Black and Brown communities from fully collaborating on initiatives to eradicate the social disparities we both face.

The trip allowed attendees – including staff, board members, fellows, and partners – to absorb facts, hear first-hand accounts of American history, and debunk long-standing narratives designed to prevent tangible progress. The time shared was an effort to go deeper into the experience of Black Americans and Afro-Latinxs of the south while equipping us with important tools to continue to advance equity on the path to justice and liberation for our intrinsically connected communities.

“A while later, I am still processing. This trip just opened the door – now it is my responsibility to continue the exploration of this part of American history”, said Lina Cardona, manager of membership operations for ABFE. “It was a privilege to have this experience in community because it provided a supportive environment to take in such heavy material.”

The civil rights study tour featured visits to the National Center for Civil and Human Rights Museum, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s gravesite in Atlanta, Georgia, The Legacy Museum, and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. In addition to site visits, each day participants were inspired and moved to action through presentations and panels of civil rights leaders, change-makers, and icons.

The trip was further enriched by the guidance of Ms. Minnijean Brown-Trickey, one of the Little Rock Nine students that integrated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957, and Ms. JoAnne Bland, co-founder and former director of the National Voting Rights Museum and one of the youngest activists to participate in the Civil Rights Movement in Selma, Alabama.

Their firsthand accounts of abuse, racial terror, and activism served as the backdrop and provided additional context to our experience as we traveled between Atlanta and Montgomery. Their leadership and participation highlighted the importance of centering first-person narratives and creating space to accurately tell the stories of Black Americans. This narrative change work is critical to developing solutions to advance racial equity and social justice.

Black America, like Latinxs, are not a monolith. It is comprised of people from diverse backgrounds. ABFE staff includes first and second-generation Caribbean people, first-generation African expats, and employees currently living in the southern states, as well as other parts of the U.S. Each staff member processed the complexities of slavery, race-based violence, Jim Crow laws, and mass incarceration through the lens of their personal heritage. ABFE trainer and advisor Kyumon Murrell, born and raised in NY – far removed from the confederacy ─ was surprised to learn that 50% of New Yorkers at one point were enslavers.

“Growing up just steps away from the ocean in Puerto Rico has had such a profound impact on my identity. It was jarring to see it in a new light at the EJI Legacy Museum— as the vessel for the transatlantic slave,” shared Ana Marie Argilagos, president & CEO of HIP. “12.5 million Africans were brought to the Caribbean, Latin America, and the U.S. Latinxs have to reckon with this truth and with the legacy of violence that persists through systems designed to commodify people. We cannot overcome what we refuse to acknowledge.”

“What many people don’t understand is that Latin America had more enslaved people shipped there than in the entire history of the slave trade in the U.S. White supremacy and its colonizing tactics of fear, rape, genocide, and enslavement were perfected with indigenous communities first, with the arrival of the Spanish, then the arrival of enslaved Africans,” noted Jazmin Chavez, HIP’s vice president of innovation, equity, and communications. “This system was transported to the United States once those ports were established and this traumatic tragedy continued. We have a shared history, a shared memory of this trauma, yet we don’t confront it, we don’t acknowledge it because of our own anti-Blackness and anti-indigeneity in our community and the trauma and fear we carry for being ‘othered’ in America.”

Unfortunately, it was evident that the civil rights movement was an unfinished agenda and that the same tactics used then, continue today. From gerrymandering to voter intimidation and race-based violence, our collective communities continue to be marginalized by systems of white supremacy. And yet, the same tactics to organize communities of color for political representation and self-determination also continue today as organizations in the south register and organize communities of color and voters.

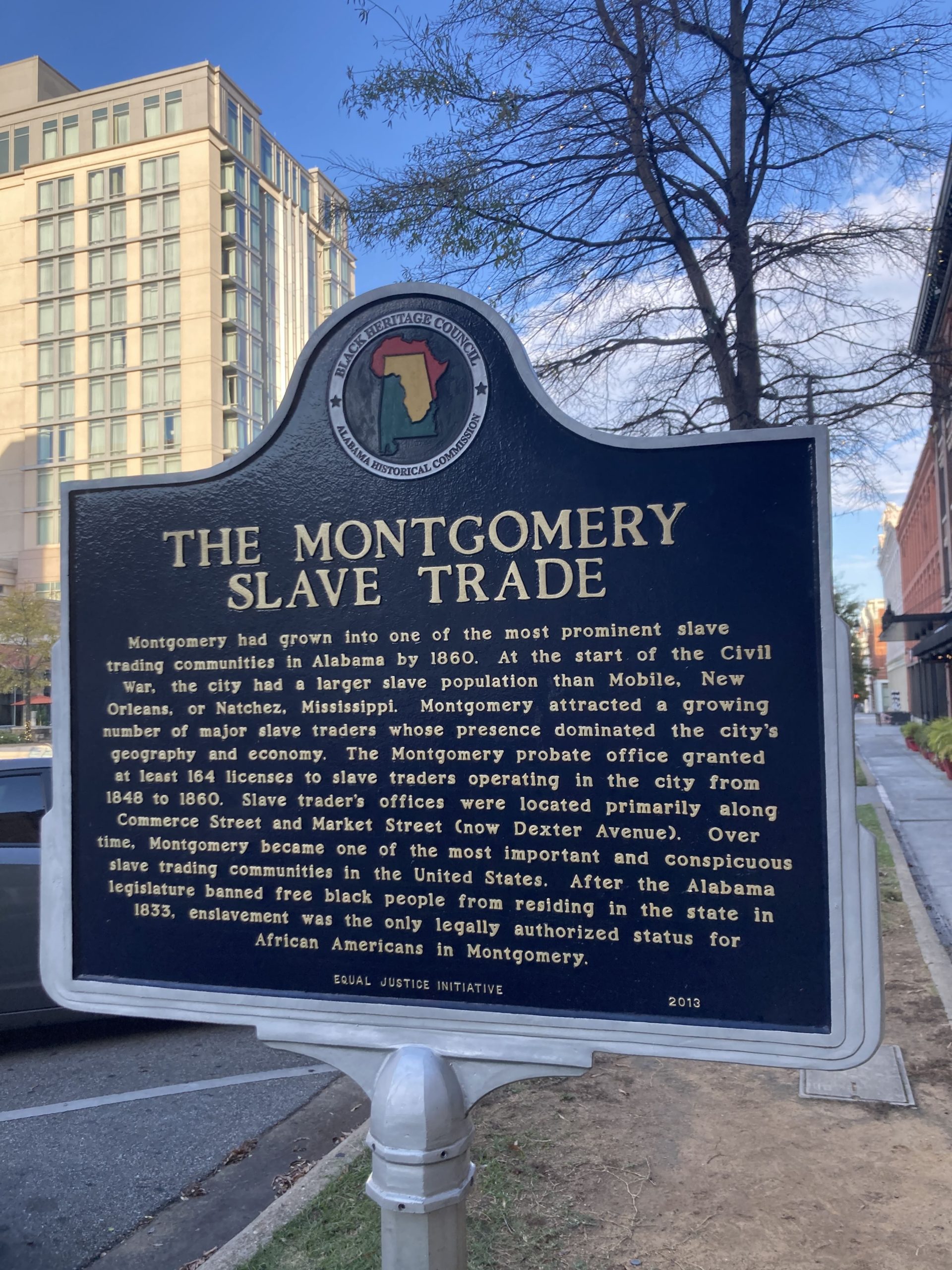

In Montgomery, Alabama, Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative said to us, “The real evil of slavery was the narrative that justified it, creating an ideology of white supremacy that persists today.” This ideology contributed to the evolution of enslavement to segregation to what is now the mass incarceration of Black men as well as the detention and separation of asylum seekers, migrants, and their families. He highlighted a system that continues to target and profit from Black and Brown bodies.

“The National Memorial for Peace and Justice was a poignant display of the impact lynching and racial terror has had county-by-county in the United States,” said Michell Speight, ABFE chief of staff. “Lynchings involved accusations of minor offenses, sometimes an arrest, followed by an angry mob that publicly hung and employed other forms of extreme brutality, such as torture, mutilation, decapitation, and desecration. “EJI’s commitment to truth-telling, in a city like Montgomery, Alabama is an example of how communities can start to honestly examine racial history by acknowledging the facts of these public spectacles that celebrated systems of white supremacy. Approximately 4,500 African American men, women, and children are memorialized at this site, but the actual number of victims that were tortured and murdered by white mobs remains unknown.”

One of the main ideas that resonated throughout the trip was the notion of “collective memory” versus individual memory and the importance of truth-telling. Bryan Stevenson explained the power of telling the truth, of reframing the conversations around harm & repair in order to move hearts and minds toward our vision of liberation. Alejandro Avilés, associate director of network engagement at HIP shared that, “we need a fundamental mindset shift of how we understand challenges and solutions in the South – from policies to infrastructure to incarceration. We are facing the remnants of intentional multigenerational roadblocks within systems designed to preserve a racial hierarchy. So, how can we achieve justice over one or two grant cycles?”

When we tell the truth and reconcile with what was lost because of the structures and legacy of white supremacy – visualizing reparations becomes possible. For example, many Black veterans and their families faced systemic discrimination in attempting to secure resources from the G.I. Bill (Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944), a law that could have built wealth and provided a range of benefits for returning World War II veterans. Or when we tell the truth about the origins and evolution of policing as a way to maintain the perceived racial hierarchy after the Civil War – defunding the police is possible. The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice memorializes the more than 4,000 Black people who were lynched in the United States. The Memorial provided a visceral example of how the system of policing was designed to perpetuate complicit practices that undermine public safety and create harm and how these practices continue to this day. Imagine the impact it would have on our communities if we were to reprioritize the disproportionate resources law enforcement receives versus social services, education, and more.

For some, the trip reaffirmed their commitment to advancing multiracial coalitions across the south. Bayoán Rosselló-Cornier, associate director of power building & justice at HIP shared how grateful he was to have grassroots leaders from the region present to share “the ways they are challenging attacks on hard-won rights, approaching civic engagement across citizenship status, and confronting anti-Blackness in the Latinx community.”

The trip highlighted the importance of alliances and what they can bring when we lead with compassion and empathy, we can enter them with an open and shared understanding of how our experiences are connected. We utilize empathy to connect deeply with a historical legacy that continues to perpetuate harm in our communities. “Understanding each other’s history is the first step – but how do we apply that historical lens to inform future work?” said T.J. Breeden, ABFE’s director of programs. “We need to dig deeper and address biases within each of our communities so we can collectively address social disparities as a whole instead of as individual communities.”

ABFE and HIP have rooted our visions of success in abundance and will continue to confront the false narratives of scarcity that would have us believe otherwise. The philanthropic sector brings its own daunting limitations, and yet, we have to acknowledge the power and responsibility we hold to move philanthropy forward, despite how long the road to justice, reparations, and equity may seem. It is why we support the funding of the ecosystem of multiracial movements and organizations aligned with our vision because the path to liberation and justice is not solely based on victories. It is also why we seek to learn of the stories and work of leaders like Ms. Minnijean Brown-Trickey and Ms. JoAnne Bland, to build upon what they’ve already provided for us. It is about taking the torch and becoming conduits of power so that the next generation doesn’t have to fight as hard for the world we know is possible.