A Journey to the Crystal Frontier

Reflection on visits to Matamoros, Tamaulipas, and El Paso, Texas

This is the first installment of a blog series that reflects on the current humanitarian conditions of people on the move and the ecosystem that supports them across overlooked regions. Brought to you by HIP's Forced Displacement and Migration Program.

“We are already here, that is what matters” Nico, a young Venezuelan migrant tells us as he searches for a coat, among the pile of clothes brought by people from the community of El Paso, since their destination is New York City, where they have been told that it gets very cold at this time of year.

Their migratory routes, nationalities, and reasons for migrating are diverse, but the risks that migrants face, as well as the stories, which most tell us that they prefer to forget because “they are already here”, are very similar.

Despite the dangers that people continue to encounter on the various migratory routes across the continent, the situations that they go through in their countries of origin also continue to worsen. These have been the reasons for continuous expulsion, mainly of the Venezuelan population, due to the social, political, and economic crisis that Venezuela has been facing for many years has led more than 6 million people to leave their country, that’s approximately 20% of its population.

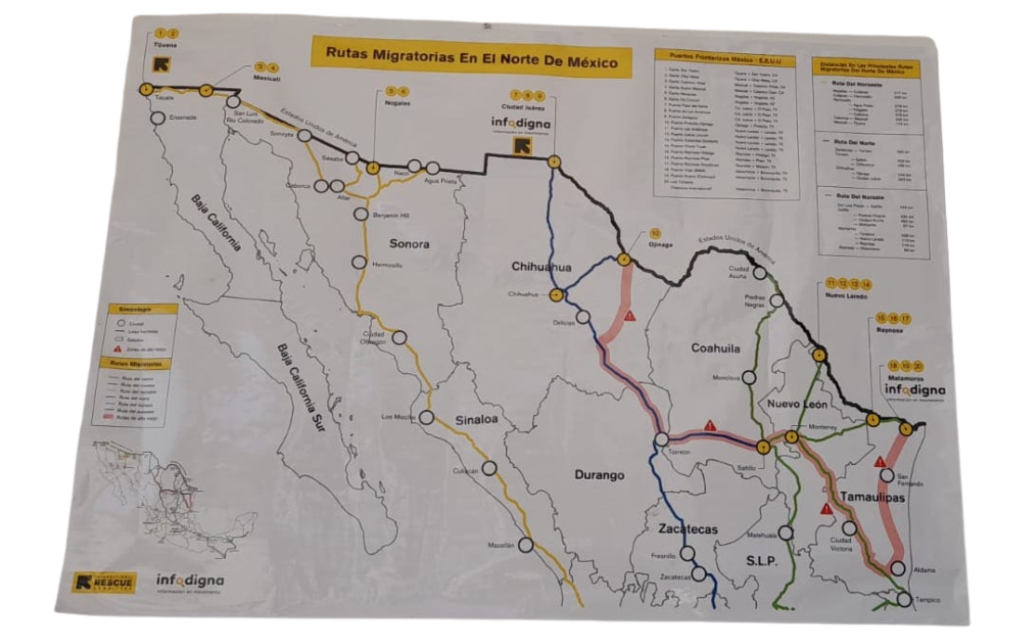

The route

There are places along the route that are extremely insecure for migrants, such as the Darién region, a thick jungle on the border between Colombia and Panama, commonly called the “Darién plug.” Across this 100 km stretch, people do their best to avoid the risks that come along with crossing the jungle, as well as the various forms of violence (sexual assault, among others) that they encounter, as it is a territory that is not monitored by any authority and with little presence of humanitarian organizations.

The arrival to cities in Panama, as then is the passage through Costa Rica, is known as a space of greater tranquility, where they receive support from the population and various organizations. Subsequently, for the journey through Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, they are once again a risk, in this case, due to the violence experienced by these countries, which also has driven the expelling of their own population. For the Venezuelan people on the move, it also represents an expense, since according to the testimonies of people like Nico, and various news reports, countries like Nicaragua and Honduras are charging between 150 and 240 dollars just to cross.

Finally, there is Mexico, which continues to be the most difficult country to cross. The violence is considerable and the abuses migrants experience come from various sources. From extortion by coyotes, and a lack of security because of criminal groups, to abuse by immigration agents, police, and military (including the National Guard), who know how difficult it will be for someone to report them.

“I was afraid since I was coming with my daughter and my wife, and you know what they do to women on the way,” shared Rúben, a former Venezuelan police officer, referring to the heightened risk of sexual abuse and various forms of sexual violence migrant women face.

It should be remembered that before Mexico and several Central American countries began to require visas from Venezuelans, a large part of these scourges were avoidable. With the imposition of visas from the beginning of 2022, and the proliferation of measures solely aimed at controlling the flows, regular and safe options to migrate have increasingly diminished and instead increased the risks.

The Border

For obvious reasons, another point that generates a lot of anguish among migrants and refugees is the border between Mexico and the United States. The fate of migrants in achieving their goals, such as accessing US territory to seek asylum, is still subject to racist policies such as Title 42. This is evident on the border between the Mexican state of Tamaulipas and the part of Texas known as Rio Grande Valley, where thousands of Haitian people hope to cross an international bridge asking for an exception to Title 42 (a policy by the government for cases of "vulnerability").

In Reynosa, the Catholic sister in charge of the Casa del Migrante explained to us that “we serve all migrants of different nationalities, families, men, women, adolescents, and children, and we have adequate dormitories and services for each group. Right now the house is full, especially with women and children from Haiti, because they have organized themselves in such a way that the men decided to stay outside, exposed to the weather and to those who seek to target them. The other shelters are also full and there are still people on the streets. We have rented some rooms in the neighborhood for families and we give them supplies because it is difficult for someone to rent directly from them.”

The organizations in Reynosa collaborate closely to meet the humanitarian needs of the migrant and asylum-seeking population, but more support is always needed. For example, although an additional bedroom is already being built in the Casa del Migrante, all the beds, mattresses and sheets are not yet available. Food, hygiene products, cleaning, and medicines are never enough. With a smile, a volunteer shared with us, “all in all, we are glad to see that when the migrants spend some time with us, sometimes they put on a little weight.”

The arrival

At different points of the border, almost every day, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) allows a group of people to approach the international bridge in Reynosa, with the request for an exception to Title 42. Although this moment means they are finally able to cross the most feared border, there are still many challenges ahead for them to be formally recognized as refugees or assigned another form of migratory protection. Sister Norma of Catholic Charities Rio Grande Valley in McAllen, Texas told us that planes leave daily to deport migrants to their countries of origin.

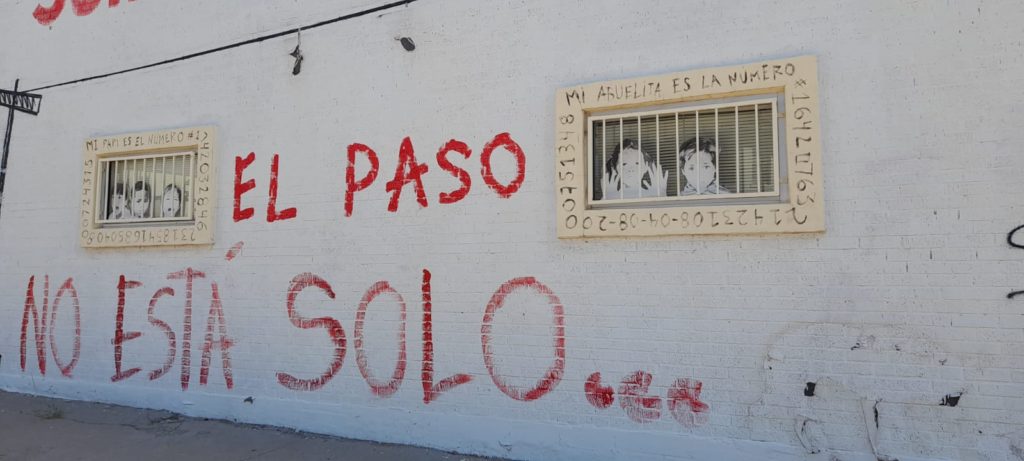

To cross the border and already be in the United States offers relief for the migrant population, as several people with whom we were able to talk in El Paso, Texas told us, despite the difficulties they face when being detained in the migrant detention centers.

In El Paso, reports of the governor have shown how he recently used the migrant population within the state to generate political pressure. Taking them on buses to states governed by the Democratic Party or as was the case of two groups of migrants, they were taken to the door of the house of Vice President of the United States, Kamala Harris, in Washington DC.

Outstanding debts continue

On October 12, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced that Venezuelans who enter the United States at ports of entry, without authorization, will be returned to Mexico, expelling the population under the use of Title 42.

Under the same announcement, they opened a legal channel to receive 24,000 Venezuelans who are able to meet certain requirements, like not having passed irregularly through Panama or Mexico. Protection needs are not listed among the requirements.

Although this news is well received by many, because 24,000 displaced Venezuelans may benefit, it is important to remember that the proposed number is far from sufficient considering the number of Venezuelans who arrive in the United States every month. Civil society organizations, like WOLA, have made increasingly responded to underscore just how disappointing this expansion of Title 42 is.

Between the months of August and September 2022, 58,000 people were registered as crossing the border into the United States. Therefore, it is obvious that this measure will only increase the risk for Venezuelans on the move, considering they may be left exposed, fleeing poverty, insecurity, and other difficulties they have faced in their country for more than a decade.

The governments of the United States and Mexico must develop and strengthen laws and policies that protect and include people on the move. For example, permanently ending Title 42 and thus restoring access to the asylum system. As we saw on the US-Mexico border, organizations are struggling with the consequences of these policies, and with almost no support, they bend over backward for people like Nico, Ruben, and their families. Policies must be formulated with a focus on human rights. Only then can we begin to draw a path that is safer for people on the move.

We thank our grantees on the front line who welcomed us, and we invite you to support the humanitarian organizations working on the border:

- Casa del Migrante de Matamoros

- Casa del Migrante de Reynosa

- Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley

- Derechos Humanos Integrales en Acción (Ciudad Juarez)

- Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center (El Paso)

- Iniciativa Kino para la Frontera (Nogales, Sonora and Arizona)

- Centro de Atención al Migrante Exodus (CAME) (Agua Prieta, Sonora)

- Casa del Migrante Tijuana

- Espacio Migrante en Tijuana

- Casa Arcoiris (Tijuana)

- Instituto Madre Asunta (Tijuana)